Pivotal Voting Moments In United States History

There is a growing chorus of lamentations in America today… elections have lost their integrity, we have strayed from the intent of the founding fathers, the public space is full of misinformation, foreign interference, Russia, Putin, Facebook, etc. Why can’t we just go back to the old days, when everyone followed the rules and respected each other?

It may surprise you to know that while electronic communication makes it appear that there is more mischief surrounding elections than ever before, America has a rich history of gamesmanship and political shenanigans dating all the way back to her beginnings. There have always been and will always be people so certain of their ideas and philosophies that they are willing to compromise any system they must to ensure the implementation of those ideas and philosophies. George Washington warned of the dangers of partisanship in his 1796 Farewell Address, but there are distinct advantages to this double-edged sword. Without the fiercely anti-federalist arguments of Thomas Jefferson, for instance, the US Constitution would not have the sacred individual protections afforded American citizens by the Bill of Rights.

It can be convincingly argued that a competitive arena of ideas better supports the forming of a more perfect union than a peaceful echo chamber of unchallenged absurdities and largesse, but the key to ensuring a peaceful transition of power when those ideas are diametrically opposed is a system that is not only impervious to gamesmanship and political shenanigans, but trusted by all.

Early Republic Expansion of Franchise

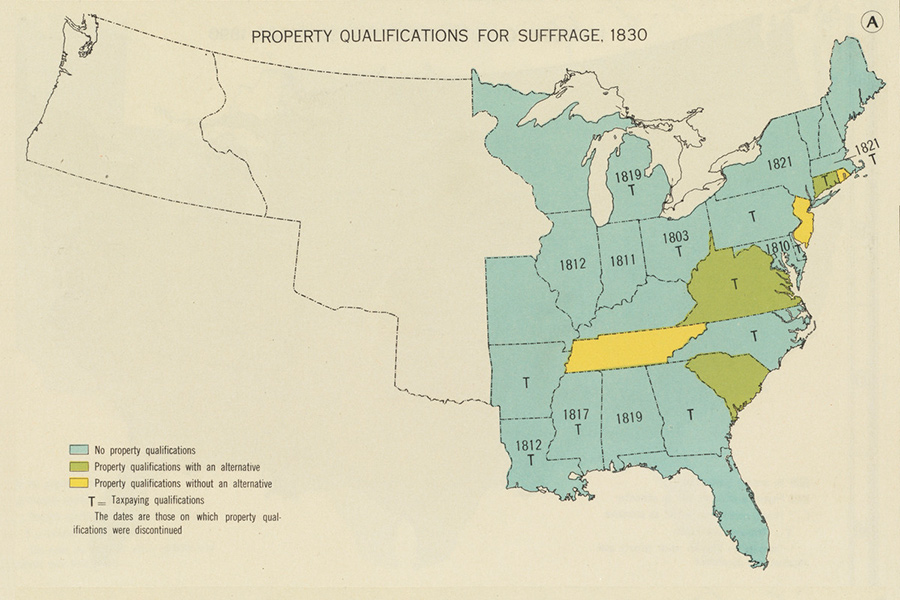

In the first decades of the Republic, different states gradually changed requirements on who was able to vote, in response to the dramatically increasing population and growing public pressure. One of the most substantial restrictions had been the requirement that only property owners could vote. Those who did not, known as “nonfreeholders,” included laborers, small merchants and shopkeepers, and newly arrived immigrants among others. All such individuals were, however, expected to serve in the militia. Some argued that service in defense of the community should entitle one to the right to vote. Another significant restriction was the requirement that one pay taxes to be able to vote, on grounds that those who shared the financial burden should be among those whose voices counted. By the 1840s, only South Carolina and Rhode Island still had property qualifications. Rhode Island discarded its property restrictions after the Dorr Rebellion of 1841-42. Its new constitution in 1842 extended suffrage to all adult males (regardless of skin color, a distinction chosen by the electorate at the time) except for new immigrants. Similarly, the states gradually shifted to allow the people, rather than the state legislature, to choose the presidential Electors. Only South Carolina (after 1836) still had the state legislature pick Electors, and (after 1842) required property ownership to vote.

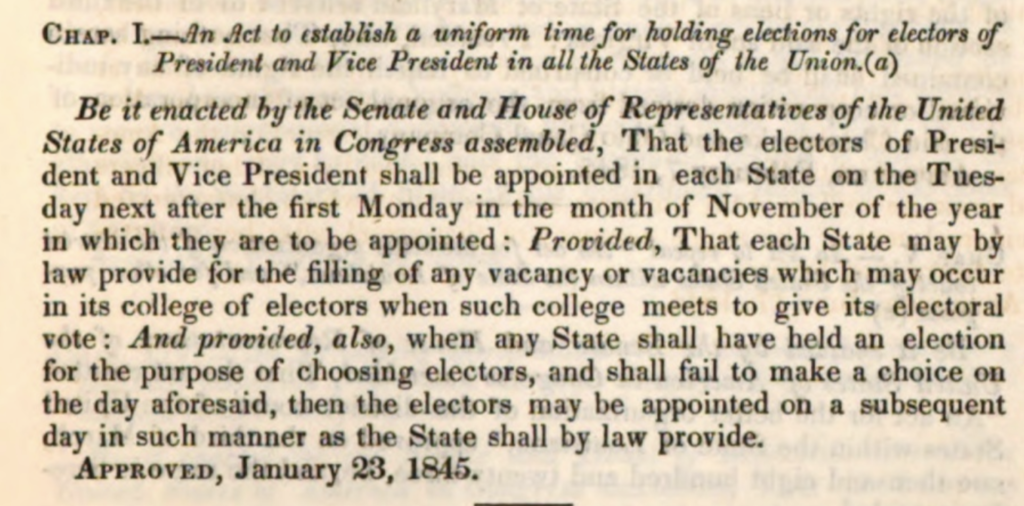

Presidential Election Day Act

The steady expansion of the franchise beyond just those with property or paying a certain tax meant that the percentage of adult males eligible to vote who actually voted in elections rocketed to very high levels. From the 1820s on, participation rates among those with the right to vote grew to upwards of 70-80% in some elections. The number of ballots cast continued to increase every year. In the 1840 presidential election, for example, an estimated 80% of eligible voters participated, and it was even higher in some states (nearly 90% of the white males in New Hampshire voted that year, for example). Even though incumbent president Martin Van Buren lost to William Henry Harrison, Van Buren received an astonishing 400,000 more popular votes than any prior presidential candidate since 1788. Concern about the growing electorate, allegations of voting fraud, and the risk that early (and perhaps inaccurate) results from one state might influence the voting in another, led to the Presidential Election Day Act of 1845. This established the first common, nation-wide day on which voting for national office would occur across the entire United States. By the Civil War, the states in the Union had made significant strides towards universal adult male suffrage compared to the beginning of the country’s history. While this would remain limited to a certain slice of the population (adults males, often only whites, over 21 and federally recognized as citizens), suffrage now meant that many previously voiceless now had a voice in local, state and federal affairs.

The 15th Amendment

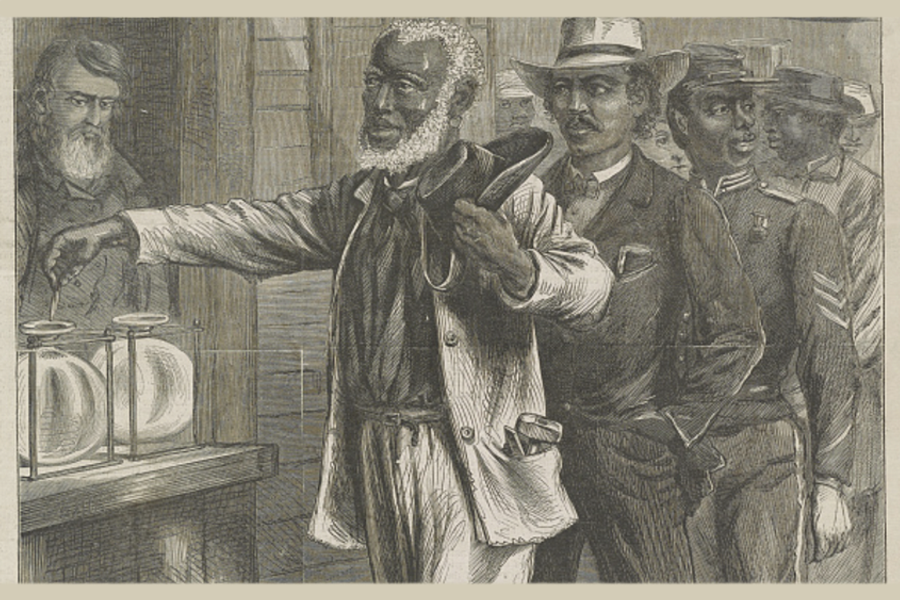

As part of the Reconstruction following the Civil War, Congress and the States guaranteed the right to vote to all male citizens regardless of race or skin color (or previous status as a slave) in federal elections through two amendments to the Constitution. The 14th Amendment (proposed in 1866 and ratified in 1868) mandated that all persons born or naturalized in the United States were citizens and that representation in Congress would be based upon the number of citizens (excepting American Indians) in the states.

Any state that attempted to block some of its males from voting would see their representation diminished in proportion to the denied voters. This was a specific effort to prevent former Confederate states disenfranchising males because of skin color or race. Any barriers that a state might erect would have to apply equally to all males in the state. The 15th Amendment, short and simple, followed two years later. It mandated that this recognized right to vote for all males, regardless of skin color or race (or previous status as slave) would apply to both the federal government and the states and thus in all elections. Congress subsequently passed several laws to enforce these amendments, but they would later be repealed. It would take a century for the promised expansion of the franchise to become permanent, and for it to extend to others whose origins lay in the Americas or Asia rather than Europe or Africa. These two amendments from the Reconstruction Congress laid important foundations and created the legal basis for subsequent challenges to disenfranchisement and expanded access to the ballot.

America and the World

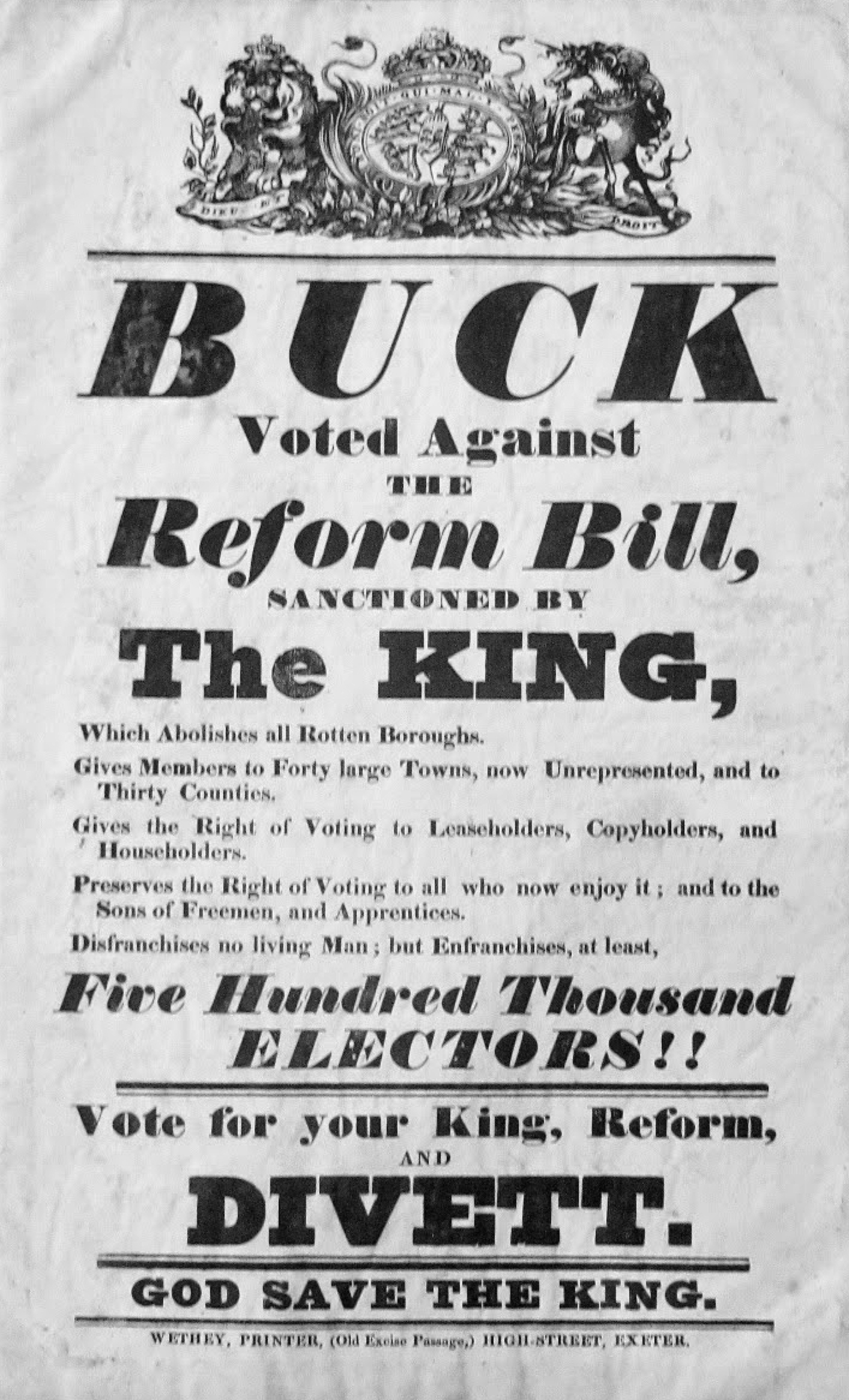

Historians also note that the U.S. Civil War—which resulted in the freeing of the slaves, the perpetuation of the union, the continuation of the unique republican experiment, and empowerment of a much larger electorate than any other country in the world—influenced in no small part electoral reform efforts in other countries. Among these was the dramatic doubling of the voting population in Britain with the Second Reform Act (1867), whose authors pointed specifically to the United States as part of their motivation.

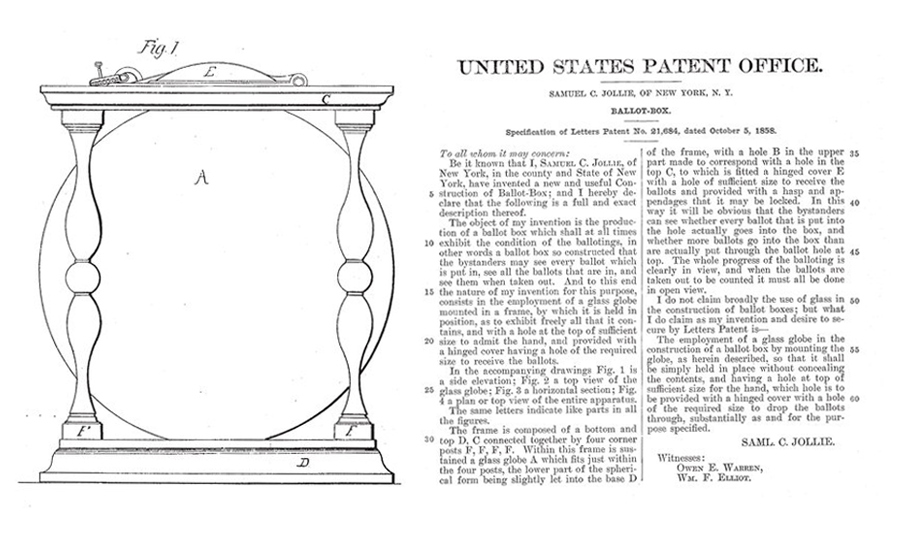

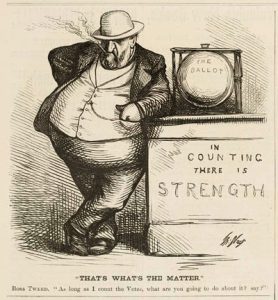

Secret Ballot / Australian Ballot

The Gilded Age of the late 19th century saw election fraud and general political scandal that generated significant public backlash. One important part of this backlash was the push to protect the voting process itself. The result was the widespread adoption across the United States of the so-called “Australian” or secret ballot. This is the system of using uniform ballots printed and provided by the government, and which voters can use to mark their preference in privacy without others observing their vote. It was first introduced as a system in Australia (in the states of Victoria and South Australia) in 1856 and in Great Britain in 1872. After the 1884 United States presidential election, with widespread claims of voter fraud and delayed election results, states widely adopted it.

What made this different from what had been used before were the following: a closed ballot box (no longer a clear glass bowl) into which the voter himself (no longer an official) would place the ballot; a uniform ballot with all recognized candidates listed, instead of separate ballots printed by different candidates and brought to the polls; and a private voting space instead of the casting of ballots in public or (as done in some places) by voice. This made it harder to arrange for voters to cast multiple ballots; harder to intimidate voters at the moment of casting their ballots; harder to stuff the ballot box with privately printed ballots; and harder to bring ineligible voters to cast ballots. These were low technological and procedural changes, implemented specifically to address rampant (and widely recognized) voting corruption in local, state, and national elections at the end of the 19th century, and highly effective. By 1909, more than forty states had adopted it. Only two were completely opposed. As states adopted it, confidence in these elections grew, and while there would still be corruption, it was nowhere near what it had been in those tumultuous times.

What made this different from what had been used before were the following: a closed ballot box (no longer a clear glass bowl) into which the voter himself (no longer an official) would place the ballot; a uniform ballot with all recognized candidates listed, instead of separate ballots printed by different candidates and brought to the polls; and a private voting space instead of the casting of ballots in public or (as done in some places) by voice. This made it harder to arrange for voters to cast multiple ballots; harder to intimidate voters at the moment of casting their ballots; harder to stuff the ballot box with privately printed ballots; and harder to bring ineligible voters to cast ballots. These were low technological and procedural changes, implemented specifically to address rampant (and widely recognized) voting corruption in local, state, and national elections at the end of the 19th century, and highly effective. By 1909, more than forty states had adopted it. Only two were completely opposed. As states adopted it, confidence in these elections grew, and while there would still be corruption, it was nowhere near what it had been in those tumultuous times.

The 19th Amendment

The push for granting women the right to vote in federal elections intensified in the end of the 19th century, and several states granted women the right to vote. Though an amendment had been drafted in 1878, women’s suffrage was a hotly-debated national issue for the next forty years. In 1918, President Woodrow Wilson endorsed the idea of a constitutional amendment, which bolstered the efforts of suffrage groups. The House passed this amendment on May 21, 1919, followed by the Senate on June 4, 1919. Fourteen months later, 3/4ths of the states had approved it as well, and in August 1920 the Constitution gained the 19th Amendment. Women who were citizens, regardless of race or color, would have the right to vote in federal elections.

Snyder Act

This law provided the federal legal basis for American Indians to participate in national elections by granting citizenship to all Indians. Prior to this, though some states did permit American Indians to vote, not all did. The 15th Amendment (1870) was not seen to apply to Indians generally across the United States because under its imprecise language they were not considered citizens. Military service by Indians in the U.S. Army during World War I helped convince many that citizenship and full civil rights—including suffrage—was appropriate and just. It would take another forty years for all states to remove certain restrictions, such as poll taxes, to comply with the law. Incredibly, it was not until the Voting Rights Act (1965) that the last significant barriers to full voter enfranchisement came down.

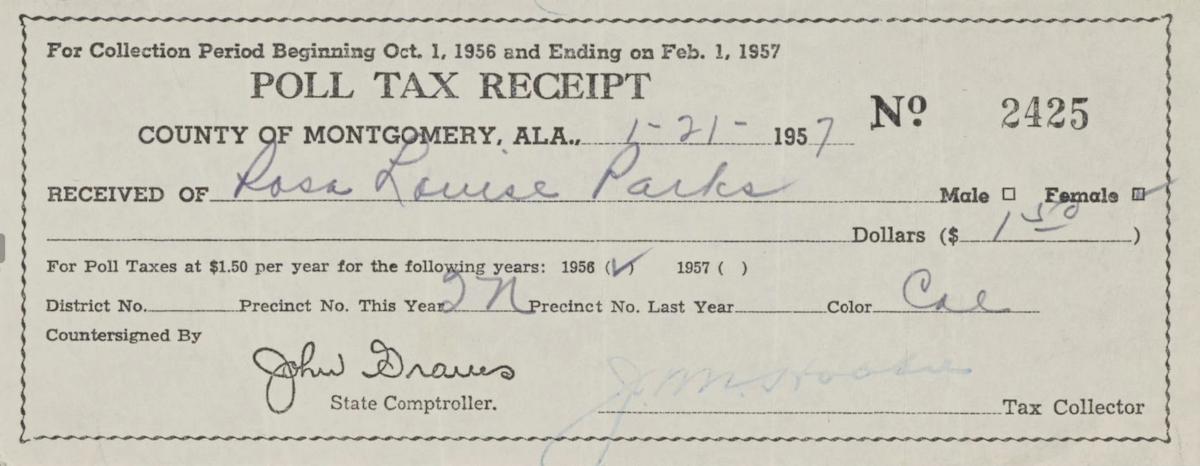

The 24th Amendment

One of the oldest restrictions to the ballot in the United States had been an expectation that a person casting a ballot was also a taxpayer. From the 17th century onward, colonies, and then states, frequently used a general per-adult tax, levied in different ways, in order to fund government operations. Poll taxes continued to be a mechanism for states to obtain revenue well into the 20th century. Pennsylvania, for example, only repealed its poll tax used for revenue purposes in 1933. But states could and did mandate payment of the poll tax as a requirement for ballot access. In the south after Reconstruction, this allowed states there to bypass the 15th Amendment (1870). It had the dual effect of disenfranchising both blacks and poor whites dramatically. It would not be uniformly enforced, and payment rules could be onerous if not impossible to meet. Attacks on the poll tax as a voting requirement intensified in the early 20th century from civil rights reformers as well as populists. In Louisiana, for example, Governor Huey Long championed the elimination of the poll tax and achieved that in 1935. The following year, the number of registered voters in the state had nearly doubled. As attention to civil rights intensified in the late 1950s, the disenfranchisement caused by the poll tax became a specific target. Congress approved the text of the amendment in 1962, which prohibited poll taxes from being a barrier to participation in federal elections, and the states ratified it by 1964. A subsequent decision of the Supreme Court in 1966 (Harper vs. Virginia Board of Electors) extended it to all states.

The Voting Rights Act

This law, a major piece of civil rights legislation, addressed several issues involving access to the ballot. Designed specifically to revive enforcement of the 15th Amendment (1870) and improve upon the Civil Rights Act (1964), it prohibited barriers to the ballot on the basis of race or skin color in all elections, federal through local. Among other provisions, it forbade specific tests or restrictions, such as the ability to read or write, to demonstrate knowledge, to have a specific moral character, or to have to be vouched for by others. It notably blocked rules that restricted access based on a person’s language of education (meaning that ballots might have to be in languages other than English). It reiterated that poll taxes could not be used as a barrier to participation in elections. It established that committing fraud in registering or voting, or conspiring with another to commit fraud in registering or voting in federal elections, was a crime. It also made it a federal crime to destroy or alter the ballots themselves in any election for one year after an election had occurred, meaning that the ballots needed to be retained as official record of the election. This brought to an end the restrictions on the franchise imposed after Reconstruction by states attempting to block the 15th Amendment (1870), but in a way that was universal, across the country, in opening the franchise to all adults over the age of 21.

The 26th Amendment

The minimum age for suffrage became an issue in 1942, when Congress lowered the draft age from 21 to 18 during World War II. This meant that adult males could be conscripted into war by the federal government but could not make political choices about that war through federal elections. Though Congress recognized the issue, there was no serious effort to resolve the dilemma. Only the State of Georgia amended its constitution to lower the voting age to 18. The issue emerged again during the Korean War, but Congress again could not reach an agreement on what to do. Still, the issue remained potent. President Dwight Eisenhower called in 1954 for the lowering of the age to vote. By referendum, the State of Kentucky lowered its voting age to 18 in 1955. The states of Alaska and Hawaii each joined the union in 1959 with lower voting ages in their constitutions than the national age of 21. With the Vietnam Conflict, the issue intensified. President Lyndon Johnson publicly called in 1968 for the age to be revised. Congress then the following year, with the support of President Richard Nixon, considered a draft Constitutional Amendment to do this. Senator Ted Kennedy offered an alternative path through statute rather than an amendment, attached to the legislation extending the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and this won out. However, the Supreme Court ruled this path unconstitutional in a subsequent legal challenge. In response, Congress then proposed and approved what became the 26th Amendment that lowered the age to vote from 21 to 18. Four months later, the states had ratified this amendment and it was permanent.

Voting Accessibility for the Elderly and Handicapped Act

To improve the ability of those with physical challenges to participate in federal elections, Congress required states through this law to improve the accessibility of voting registration locations and the ability of the elderly or those with physical limitations to participate in federal elections. This included enhancing their ability to vote through absentee ballots or in a manner other than in person.

This legal protection of accessibility would expand through the subsequent Americans with Disabilities Act (1990).

Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act

Until 1942, there was no single federal law on how soldiers and sailors away at war could vote. During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln had permitted soldiers to return home on furlough to vote if their states did not permit or facilitate absentee voting. During World War II, Congress attempted to provide deployed soldiers and sailors the chance to vote in federal elections. After the war, there were two efforts to improve access to the ballot for those serving their nation abroad with varying success.

The 1986 Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act brought together the two previous laws [(the Federal Voting Assistance Act (1955) and the Overseas Citizens Voting Rights Act (1975)] to require states to permit members of the uniformed services, family members, and civilians no longer residing in the United States to register and vote by absentee ballot for all federal elections. Subsequent laws since 1986 have amended and refined the requirement, but the basic provisions provide the opportunity for U.S. citizens absent from the country for many different reasons to participate nonetheless in the federal elections.

The 1986 Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act brought together the two previous laws [(the Federal Voting Assistance Act (1955) and the Overseas Citizens Voting Rights Act (1975)] to require states to permit members of the uniformed services, family members, and civilians no longer residing in the United States to register and vote by absentee ballot for all federal elections. Subsequent laws since 1986 have amended and refined the requirement, but the basic provisions provide the opportunity for U.S. citizens absent from the country for many different reasons to participate nonetheless in the federal elections.

For Further Reading:

The following list of books should be seen as recommendations for further exploration, not a definitive list of scholarly work on the history of pivotal moments in the ballot process in the United States. It will be updated over time.

Engstrom, Erik J. and Jason M. Roberts. The Politics of Ballot Design: How States Shape American Democracy (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. Updated Edition (HarperCollins, 2014).

Foner, Eric. The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution (Norton, 2019).

Keyssar, Alex. The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (Basic Books, 2009)

McCool, Daniel; Susan M. Olson; and Jennifer L. Robinson, Native Vote: American Indians, the Voting Rights Act, and the Right to Vote (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Sibley, Joel H. The American Political Nation, 1838-1893 (Stanford University Press, 1991).